Enough 'Anthropocene' nonsense т we already know the world is in crisis

This article by , Professor of Marine Geology at the School of Ocean Sciences and Director of the , was originally published on . Read the .

This article by , Professor of Marine Geology at the School of Ocean Sciences and Director of the , was originally published on . Read the .

At a public seminar at a respected university in Scandinavia on how to promote cross-disciplinary research last year, the dean of one of the faculties passed the comment that тnow we are living in the Anthropocene, everything we see around us, everything in our environment, we realise is the result of human activityт.

This, of course, is nonsense. The reach of human activity is demonstrably profound, affecting nearly all biogeochemical cycling within the Earth system, but to attribute all the changes we observe to human activity is wrong; humanity has no control over the output of solar radiation by the sun, the astronomical position of the Earth, or the internal processes that drive plate tectonics and volcanic activity. All three profoundly influence humans but operate entirely independently from human activity.

I could have chosen many other examples. The sad fact is that the adoption of the term т informal, as yet, but nevertheless clearly viral т is misleading. But it is worse than that; it has stimulated a redundant, manufactured, debate that displaces more important scientific research and genuine discussion on climate and environmental change. It is a fad, a bandwagon, a way of marketing research as cutting-edge and relevant. At its worst it can be seen as a disingenuous means of harvesting citations under the guise of serious endeavour.

The beginning of the term

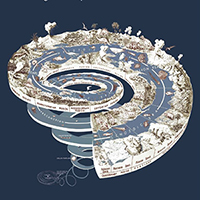

Do we need to add to the geological time spiral?: US Geological Survey http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/2008/58/The term Anthropocene was first proposed by atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer, a biologist, to denote the recognition that humans are now profoundly altering the Earthтs climate system and environment. So profoundly, in fact, that Earth scientists should name a new epoch of geological time to register this impact.

Do we need to add to the geological time spiral?: US Geological Survey http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/2008/58/The term Anthropocene was first proposed by atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer, a biologist, to denote the recognition that humans are now profoundly altering the Earthтs climate system and environment. So profoundly, in fact, that Earth scientists should name a new epoch of geological time to register this impact.

The naming of chunks of geological time was necessary, particularly so before the dawn of radiometric dating and other ways of directly measuring the age of rocks. Back then, there was no choice. Names such as тCambrianт and тPleistoceneт were invented and the time period they represented were defined in layers of rocks.

All this remains important. But it is always only a means to an end, a methodological step that ultimately helps Earth scientists to do what they should be doing; that is, to understand the fundamental processes and mechanisms that make the Earth what it is. Studying and naming layers of rock т т is not an end in itself, though reputations are made, and medals won, in deciding how the cake should be cut and what all the individual pieces should be called.

The term is now up for formal ratification of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) which requires the Anthropoceneтs base т when it started т to be defined. So there is now a тdebateт to decide where this base should be.

Is it the transition , the moment , the , or perhaps in 1960?

Without such a defined base, there can be no epoch. No doubt this debate will run and run and an is considering the matter and their latest contribution т a lengthy review that rehearses the various candidates for the base of the Anthropocene т has just been .

Quite apart from the difficulty of defining the base т the issue that so obsesses the anthropocenists т the term serves no useful purpose since it is not necessary for defining the rock record. There are plenty of ways of measuring time and establishing stratigraphies for the epoch when humans have progressively impacted the Earth system, such as measuring tree rings, radioisotopes introduced by atomic weapons testing, or counting annual layers in ice cores. We use these tools on a daily basis and have no need for the new term.

And while the anthropocenists rearrange the deck chairs, other scientists are getting on with the business of trying to understand, and do something, about the crisis we face.

![]()

Publication date: 15 January 2016